The Threads of Memory: An Interview with Amy Yoshitsu

Amy Yoshitsu, an October myma artist grant recipient, explores the systems that shape our lives, from the infrastructure beneath our feet to the unseen forces that influence our identities.

Amy Yoshitsu, the October '24 myma artist grant recipient, doesn't just create sculptures; she constructs intricate narratives that dissect the systems that shape our lives. In conversation with artist Anna Berghuis, Yoshitsu reveals how her work delves into the hidden layers of our reality – the infrastructure that supports our existence, the historical forces that have shaped our identities, and the subtle yet profound ways in which systemic oppression manifests in our everyday lives. Through a practice that spans sculpture, installation, and photography, Yoshitsu invites viewers to question the assumptions that underpin our understanding of the world, and to consider the profound impact of these interconnected systems on both the individual and the collective.

Congratulations on winning the October myma grant! Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your practice?

My name is Amy Yoshitsu and I am a socially engaged artist making sculptures and installations. I deconstruct the interconnections between power, economics, labor, and race in order to illuminate these systems’ foundational interplay with psychological schemas, emotions and interpersonal relationships. I want to contribute to building collective self-compassion and awareness by reframing experiences and conditions within historical, political, financial, and colonial contexts. I interrogate my perspective, circumstances and heritage—defined by multi-generational struggle and isolation incurred from ambitions to survive and strive within gas-lighting white supremacist patriarchal capitalism—in relation to systemic patterns, myths and power. As an Asian-American contending with inherited, conflicting duties and narratives of care-giving and achievement, I am especially interested in the conscious and unconscious positions and conditions of those whose lineages are entangled with diaspora, assimilation and imperialism.

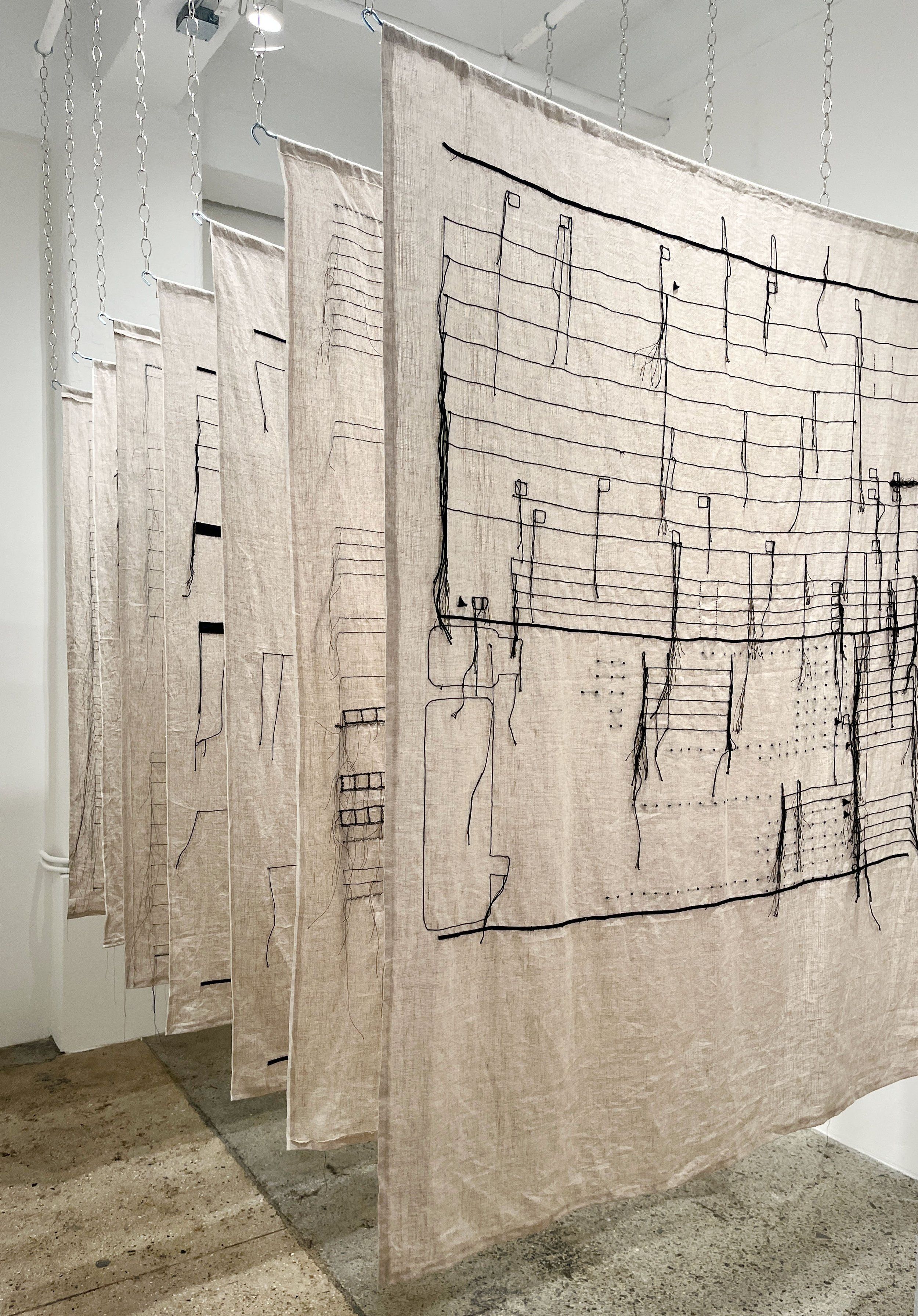

The concepts, imagery, and materials of my work are informed by infrastructure, which encompasses the act of supporting, the undergirding for creation, and the workforce maintaining our unsustainable global practices. The objects I make embody the reality that systemic forces are driven by economic and social incentives in power structures that perniciously guide our decisions and interpretations. The intersecting histories and consequences of omnipresent apparatuses—from taxation to electrical grids to the maintenance of “racecraft” (Fields and Fields)—are foundational to the tapestry of human existence. I employ sewing and textiles to interweave the effects of entrenched systems on the body, the delicate, the intimate.

I am also a co-founder and worker-owner of Converge Collaborative, a digital multimedia creative studio operating as a workers cooperative. In the work we do with clients (design, media and text-based projects) and as a creative collective (making podcasts and workshops), we center collaboration, solidarity, equity, and the belief that labor are social sites of creativity, learning and imagination. We seek to foster space and strategies for artists, especially those of color, to leverage the tools of community support and consensus-based decision-making to address some of the most difficult aspects of maintaining a creative life: economic stability, the time required to create, the social and emotional support that helps one stay committed to the craft.

Can you expand on how urban spaces and the way cities are built inspire your work? How does your exploration of humans’ desire to control their environment manifest in your pieces?

As the child of a contractor, I was attuned early to the labor, skill, economics, and social dynamics embedded both in maintaining one’s own dwelling and in the culmination of processes and projects that make our built environments. I have always been fascinated with the markers (pylon, manhole covers) of systems (electricity, water/plumbing) that undergird everyday lives and how these physical infrastructures are themselves outcomes and facilitators of political and social hierarchies. In making work often centering imagery of the creation, maintenance and decay of urban space, I have been able to unpack and articulate my obsession with the more invisible systems of capitalism, race, gender, and the effects of compounding hierarchies on our psychic, bodily and emotional lives. This has further propolled my art practice, and my contributions towards building Converge as a cooperative business and collective.

Structures within urban, suburban and even agricultural and marine landscapes are often considered the visualization of human’s separation from, power over and exploitation of nature. Not only is nature an overly broad term employed both to prop-up belief in human’s adversarial role against it and denial of our place within it, but, paradoxically, cherry-picked observations of plants and animals are used to justify and normalize human hierarchies. In my work, I prefer to think of and position those that are usually categorized as of nature and human-made as instances of interconnected systems that are currently being intervened upon and responding to—but will never be fully controlled by—humans.Thus, a unifying theme in much of my work is the toxic—and ultimately futile—desire for control, and its resulting hierarchical structures cyclically respawned from human fear and trauma.

In my photo-based sculptures, the amalgamation of twisted and contorted images of human-built interventions displayed on delicate, biodegradable material speaks both to the fragility of our physical world and to the swirl of emotions and ideas entangled in our complex society. When I place these objects, in both real and distorted manners into public and infrastructural landscapes, to make new images (series 20XX and Construct), I ask the viewers to consider the details of their surroundings, the inequitable structures that provide our everyday lives, and that our attempts to control each other and our environments are at the core of the crisis.

How does your exploration of “seeing self” intersect with the systemic and cultural themes in your work?

As an Asian-American human, I identify as being of the diaspora and a product of attempted-assimilation culture. I believe what we see around us—the landscape and buildings, the types of labor and activities, the aesthetic and technological choices and conditions—plays a role in who we are while our lineages inform how we make sense of it all.

As someone who does not drive, I have lived my life walking and weaving within urban spaces. This practice has given me time to observe, engage in metacognition and reflection, and think about how my ancestors may have taken in their surroundings while navigating the US. Throughout my life, and especially during my formative years into young adulthood, I have been acutely aware of my status on the spectrum of in-between to outsider in many realms, especially in relation to the communities that share my ethnic and racial identities. A strand of my lineage immigrated from Japan to Hawaii (before it was a US state) in the late 19th century, and my Chinese grandparents and parent, the most recent of my lineage to migrate to the US, did so around 1950. My parents, grandparents and great-grandparents (only on my paternal side) thus all engaged in mixtures of intentional and unintentional assimilation processes throughout the 20th century. I am always thinking about how their physical environments, especially in public, have played roles in these processes and their experiences in the US.

When I traverse built environments, especially in the US, I am always psychologically contending with the generational trauma of motherlands as simultaneously foreign and integrated, and my own position within histories of speculation, hierarchical race creation and colonialism. By photographing and sewing together places from all over the world that I have occupied or inhabited, I create sculptures honoring the manifestations of histories, shared needs, connected conditions. The resulting sculptures are psychogeographic maps that miniaturize and deconstruct structured space—a product of human labor, the authority of financialization, and modern survival.

Sewing and layering seem central to your practice. How did you arrive at these techniques, and what role do they play in your storytelling?

Textiles and hand and machine sewing are core to my work and my upbringing, and are part of almost every work I make. These materials and practices honor my lineage and what I was intentionally taught by my mother and grandmother, the latter of whom was a seamstress in NYC after leaving Japanese Internment from Executive Order 9066 during World War II.

I value sewing and welding as methods that facilitate amalgamating objects without requiring an in-between layer such as glue: two or more separate pieces of fabric, metal, etc are now one unit without the need for a third material that may not contribute conceptually.

Sewing can be used as a method of construction or as a means of drawing and mark making. My photo-based sculptures are held together purely through hand and machine sewing. In Return and Schedule Self-Interest, I machine sewed the lines and shapes of IRS Form 1040 and multiple Schedules.

How do you choose your materials, and what significance do they hold in the themes you’re exploring?

While the concept of each work is the largest factor in driving the material decisions, I am always thinking about environmental impact; material and conceptual consistency across my practice; aesthetic consideration; my personal resources, logistics and abilities in the moments of creation. I want to maintain my work’s conversation with the built environment and infrastructural landscapes (even if the work is not directly talking about or visualizing them) as I see these spaces as realms unto themselves that center object-making. Thus, when seeking a material, my first stop is a hardware, construction, or landscape store.

Simultaneously, I am conscious of sculpture making in relation to mass consumption and garbage culture. I save most of the remnant and test materials from my works, and have made sculptures from studio refuse in the past. I am currently working on a new series of detritus sculptures, with hardware cloth as the armature, and string and rope as the only new materials used to help create the forms.

For practical resource-related reasons, and to push against the forever culture in art, I have opted to use paper as the main material in my work about physical infrastructure. I appreciate not just the conceptual implications but the delicacy and biodegradable inevitability the paper provides to this work.

With all that said, I don’t want to subscribe to material purity culture (or purity culture of any kind). In my recent installation, Inherited and Re-made, eighty-four words, making up nine quotations, are all stuffed with poly-fil, which is ultimately made of petroleum. While I researched other potential options, no other material aligned with my resources, scale, timeframe, and the concept and intended message of the work.

Can you share how your process evolves when working on a new project? Do you begin with a clear concept, or do materials and experimentation guide you?

I always start with a concept and the resulting work is modified through research and material experiments along the way. For example, I had conceptualized the installation Inherited and Re-made two years ago and it took a year and a half to finalize the idea and produce the iteration that was featured in the two-person show, Conjuring Cruelty at Vox Populi (Philadelphia, PA) in Sept-Oct 2024.

I initially knew that I wanted to create a large soft-sculpture installation of sentences related to the process of forming beliefs, perspectives and behaviors. I am consistently inspired by the concept and book of the same name, Racecraft, which has given me a framework with which to examine, understand and grieve my own lineage. Authors Karen E. and Barbara J. Fields liken racecraft “to mental terrain and to pervasive belief. … racecraft originates not in nature but in human action and imagination. The action and imagining are collective yet individual, day-to-day yet historical, and consequential even though nested in mundane routine.” In running with this idea, I knew I wanted the chosen texts for the installation to discuss the process of race creation and include such for capitalism and environmental exploitation, as all three are deeply interconnected. In shifting my work to more directly address these invisible systems, I foregrounded letters, words, texts as visuals in themselves that are simultaneously abstract shapes, human created systems, and powerful mechanisms of behavior.

During the research phase when I was deciding the exact text for the installation, I both re-read my paternal grandfather’s memoir and kept coming back to observations, justifications, reasonings often said and remembered in my family. These words, which I had inherited, became the jumping off points for research that led me to focus on primary documents (Congressional speeches, Executive Orders, advertisements, financial records). I selected quotations from familial sources and systemic power to grow the initial concept of this work and reinforce my practice’s overall intent.

On the material side, I created a maquette while at the Vermont Studio Center (VSC), Johnson, VT, in 2023. I sewed forty square feet of plastic textile (all from single use plastic refuse) that I was planning to use in the construction of the installation in order to layer in the many concepts embedded in plastic: the dichotomy between an object’s short life of use and long life of existence; capitalist and colonial decisions at the heart of plastic’s creation; an omnipresent icon of our environmental crises.

I also wanted to include a reflective, mirror-like material to provide an aesthetic contrast with the plastic textile and to gesture towards the fact that the ideas in the work affect all of humanity. Ultimately, after many failed material experiments and sample purchases, I ended up using radiant barrier insulation (thank you again, local Ace Hardware) as the face of the quotations for the primary source document. This material provided the aesthetic requirements and added more layers of meaning including the connections to physical warmth, and water and insulation infrastructure in residential spaces.

In the first maquette, I made individual block letters to form words. Upen experimenting with how they would connect to make long sentences legible—especially knowing that I wanted the sentences to hang away from the wall—I pivoted to designing discreet words in cursive. I wrote every word by hand, digitized it, and created vector files of the words at scale in order to make paper patterns for each word. I printed close to a thousand tabloid sheets, which I (and friends) taped together, and cut out the outer shape of each scaled, cursive word. Once I had all the word patterns, the rest of the process occurred, luckily, as I had planned. I used the paper patterns to cut the back and front faces of every word. All words were built through machine sewing, hand stuffing, and hand-sewing.

While the level of planning and precision in this process can become tedious, I find it extremely rewarding (and, until the end, nail biting) when it turns out as I had imagined. I balance the rigidity of the process with other work, such as my photo-based sculptures, in which the decisions towards the overall forms are more intuitively driven and dependent on the bendability and shape of the paper.

Do you have a favorite color?

Yes, my favorite color is yellow. If you see me in person, you will most likely see me wearing (glasses, beanie, sweatshirt) or adjacent to (phone case, wallet, water bottle) something yellow. The color has been near my body longer than it has been incorporated into my art but recently exploded in visibility in my practice. In Inherited and Re-made, each sentence was delineated through being constructed with a different yellow fabric on the back and side faces. My embrace of yellow acknowledges that race is a human-made creation; it is the color-coding I am assigned to in the racial bucketing system. Yellow also has specific meanings—caution, yield, the buffer between stop and go, attention—and demarcates active maintenance spaces in the built environments. In western culture, yellow has been associated with depression, undesirability, and outsider-status. My light-eye-brain connection happens to love yellow, especially neon yellow, and I consistently find so many connections it has to multiple realms I am constantly unpacking.

What role does your environment—studio space, city, or community—play in shaping your art?

I love living in Berkeley and the Bay Area overall. I am deeply grateful to the privilege of living where I am from and having life-long connections to people and spaces. While I contend with deep unease about many personal and systemic dynamics (as many of us do), there is a peace that comes from creating, working and contributing to the community within the main home I have known.

In re-reading my grandfather’s memoir recently, I learned he had spent more time than I had understood in Northern California and San Francisco before being forced into Japanese Internment in World War II. As my connection to the region continues to grow, I remain enamoured with the landscape. In the series Construct, the infrastructural landscapes of California, in which my sculptures are digitally installed, often visualize or gesture towards human intervention amidst sky, water, grass, trees, land. I try to choose images that visually decrease the dichotomy between nature and human-made to highlight that everything, especially our problems, are interconnected.

What future projects or themes are you interested in exploring next in your art?

As I have mentioned, I’m working on completing a series of detritus sculptures. I have a lot of refuse material from recent projects that I am excited to put into more object making.They are inspired by my previous work, Yellow Anatomy (a more minimalist sculpture that also used hardware cloth as the armature and was covered in painted burlap) and The Society of the Post-Consumption (a year of studio detritus sandwiched between large plexi sheets).

After that, I am really excited to start working on a multi-material sculpture project centered on the US tax system. In 2023, I completed Return and Schedule Self-Interest, a textile installation based on IRS Form 1040 and associated Schedules.

I am also currently on hold on—but excited to complete—a large-scale installation project in which I am silkscreening my mind map on three queen duvets. The other layers of the bed sets will have visualizations related to my sleeping dream world and documentation of the infrastructure needed to complete the project.

Who are some of your influences?

Visual artists: Mona Hatoum, Agnes Martin, Theaster Gates, John Chamberlain, Eva Hesse, Nancy Rubins, Gordon Matta-Clark, Donna Denis

Writers/thinkers: Barbara and Karen Fields, Dorothy Brown, David Harvey, adrienne marie brown, Ibram X. Kendi, Mark Fisher, David L. Eng and Shinhee Ha

How do you like to spend your free time outside of the studio?

I don’t know if I would call it free time but when I am not in the studio, I am working on design projects for clients, financials and business strategy, internal communications and marketing, and more all in collaboration within fellow worker-owners in Converge Collaborative.

Otherwise, I need to get outside at least once every day. My rhythm follows the sun so I try to jog in the afternoon during winter and at sunset during warmer months. I enjoy cooking (and eating!), supporting and sharing with friends, and pulling weeds in the garden if I have time.

What are you listening to now?

A lot of different podcasts (always love Behind the News with Doug Henwood) and the band Forests from Singapore.

What’s your go-to karaoke song?

Toxicity, System of A Down

Do you remember the first piece of art you ever created? What was it like?

As a young child, I spent a lot of time painting with my mother. I remember, with the assistance of my mom, painting my name in a motif of mountains of rivers.

In high school, I remember painting with acrylics on stretched canvas but never being satisfied with just those materials. I sewed wire and guitar string into the canvas and was already identifying one of my desired aesthetics as controlled chaos.

When you encounter creative blocks, how do you push through them?

I love working on multiple projects at one time, especially when they require different approaches. As I have mentioned, some work required planning and rigorous execution during production. Other work is more intuitive and spontaneous. When I am stuck, I like to move between projects. If the block is conceptually-based, sometimes a run can help me clear my head of other distractions, think through a problem, inspire new thoughts, or at least allow me to come back to the work with a more fresh state of mind.

Which artists are you excited about right now?

Some artists I have been thinking about recently: Luis Camnitzer, Miyoko Ito, Mimi Jung, Nari Ward

Is there a show you have seen recently that excited you?

This is not that recent but two show that stands out this year in my mind (both at SFMOMA): Sitting on Chrome: Mario Ayala, rafa esparza, and Guadalupe Rosales and Zanele Muholi: Eye Me