In Conversation with Adam Liam Rose: Exploring the Aesthetics of Safety and Theater

Artist Adam Liam Rose, recipient of the August myma artist grant, delves into his multifaceted practice, investigating the intersections of state architecture, performance, and psychological manipulation.

In conversation with artist Anna Berghuis, Adam Liam Rose shares the trajectory of his artistic exploration, where state architecture, power, and performance collide. Rose, a multi-disciplinary artist born in Jerusalem and raised in the U.S., examines the darker aspects of how “safety” is wielded by state actors—often as a pretext for control, destruction, and the advancement of dubious agendas. His practice spans textiles, sculpture, installation, and drawing, each medium interrogating the visual “cheap tricks” used to pacify populations and conceal deeper threats. Rose’s critical approach invites viewers to question the aesthetics of protection, where seductive illusions mask dangerous realities.

Congratulations on winning the MyMA August Grant, Adam! Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your practice?

Thank you so much! I’m truly honored to receive this grant and I'm especially grateful to Amir Fallah for reviewing and selecting my work. I grew up in Jerusalem in the 1990s and emigrated to the United States in the early 2000s. The move really impacted how I view the world, and has deeply influenced my artistic journey. In my art, I often explore the dynamic between state architecture, aesthetics, and power. I’m interested in the theatrical elements of various “safety” structures (such as watchtowers, bunkers, government buildings, separation barriers, etc.) and how they “perform” as if on a stage. Lately, I’ve become particularly fascinated by how such structures are wielded by powerful actors to manipulate perceptions and offer false promises.

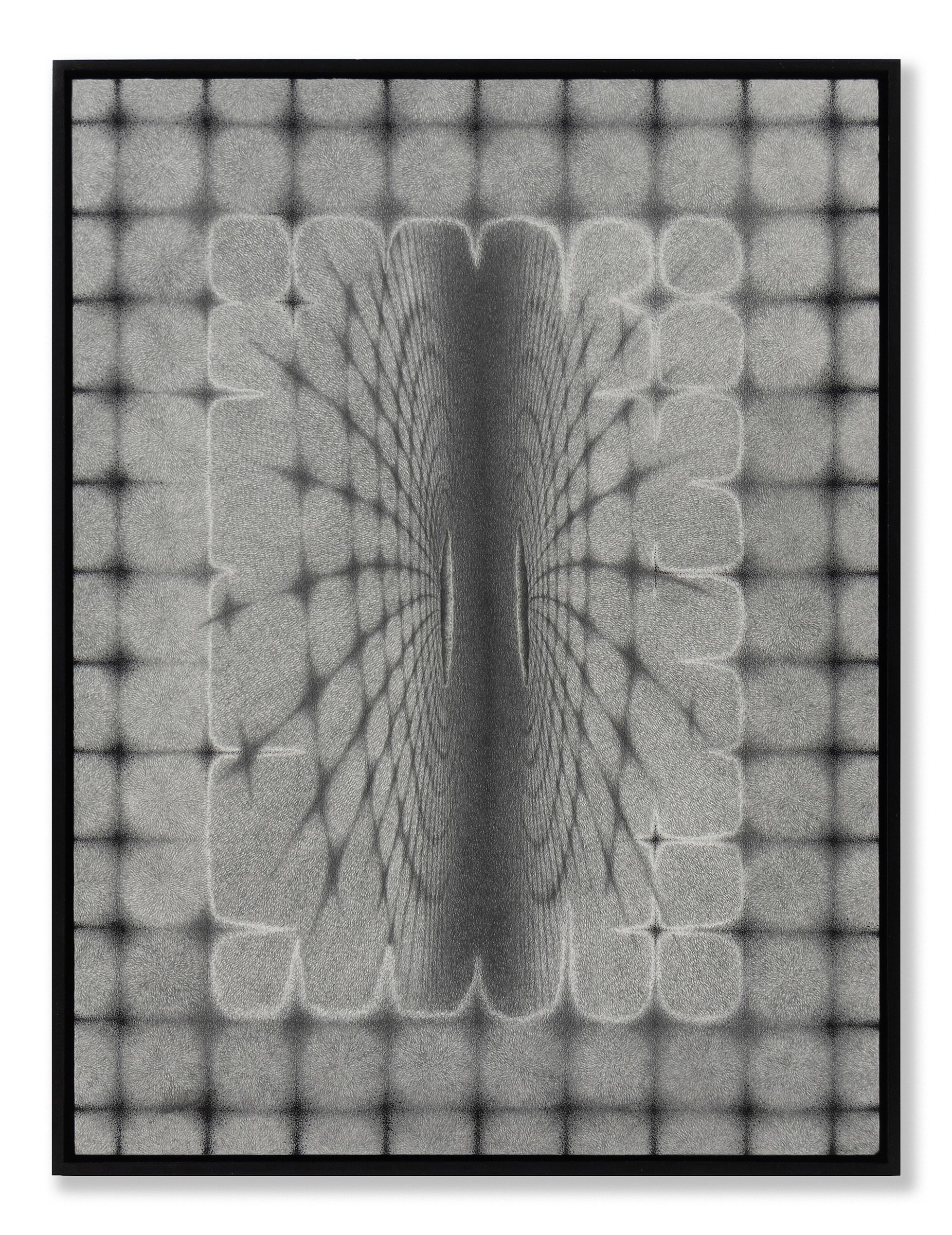

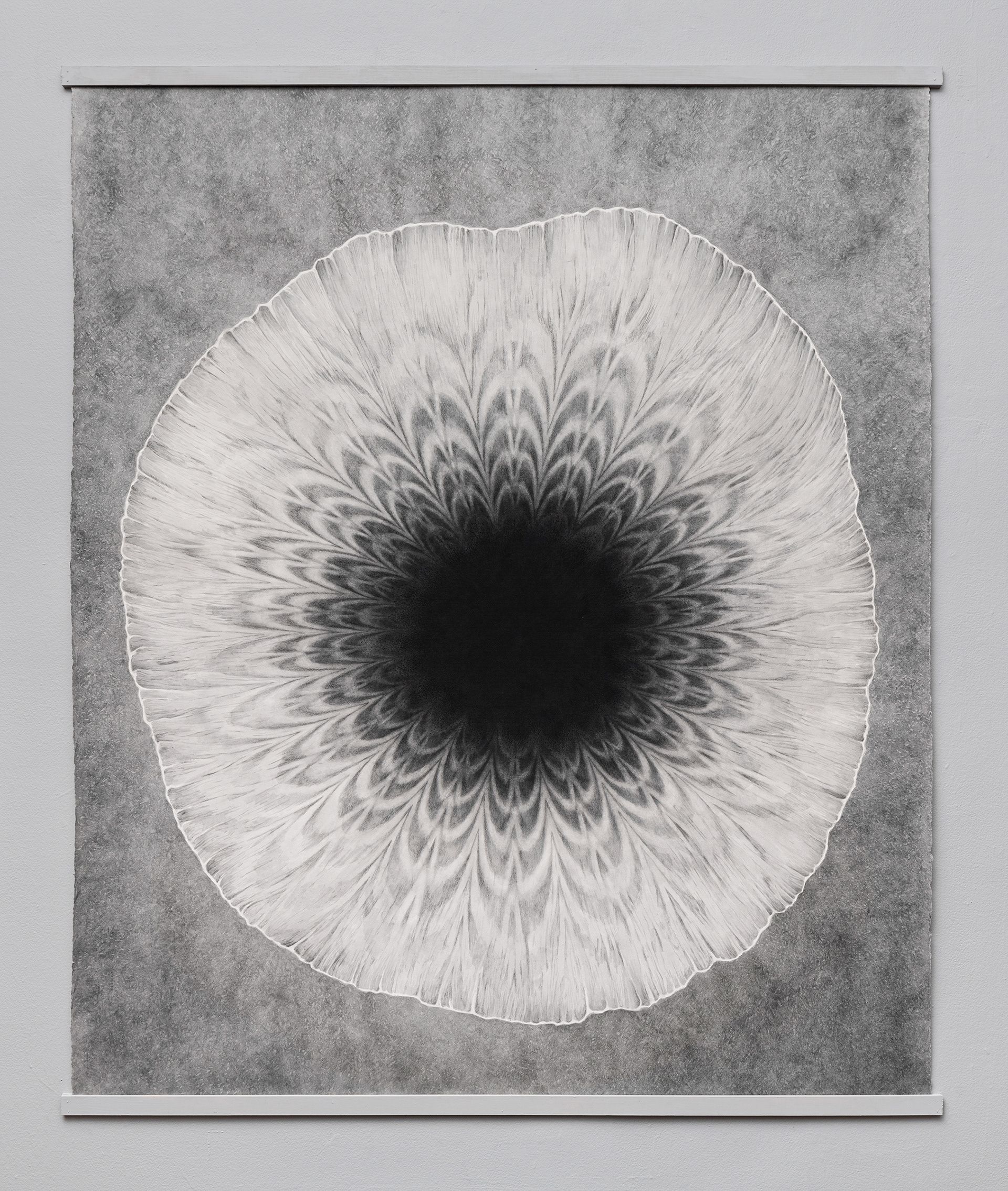

My practice has evolved over time, encompassing textiles, printmaking, video, large-scale installations, sculpture, and, most recently, drawing. Additionally, I’ve been experimenting with abstraction to delve into the more psychological dimensions of these themes.

How did you first become interested in this concept of the aesthetics of “safety,” and what drew you to investigate it through art?

As an Israeli, the concept of “safety” is deeply ingrained in our culture and closely tied to Israeli identity. My interest in the aesthetics of safety stems from various influences: growing up with this idea embedded in both American and Israeli societies, grappling with supposed existential fears, and spending my childhood surrounded by security architecture in East Jerusalem. As a queer person, I’m also drawn to contemporary discussions around “safe spaces.”

I've witnessed how the state often manipulates the notion of safety to justify horrific actions that go far beyond genuine security, advancing agendas with questionable motives. Seeing how aesthetics can be weaponized for less-than-innocent purposes has inspired me to investigate these themes through art. My goal is to awaken both myself and others to the aesthetic illusions that often mask the deeper realities of our environments.

You describe aesthetics and “cheap tricks” as methods used to soothe or distract. Could you explain what you mean by this and how it appears in your work?

I love the term “cheap tricks” because it really gets to the heart of aesthetic manipulation. I’m thinking about how optical illusions and techniques used in film, like green screen, allow viewers to suspend their disbelief and become entranced by the visuals, even though they’re aware that what they’re seeing is a trick. I’ve been curious about how similar “cheap tricks” manifest in our everyday lives. What scripts are we following to maintain a status quo?

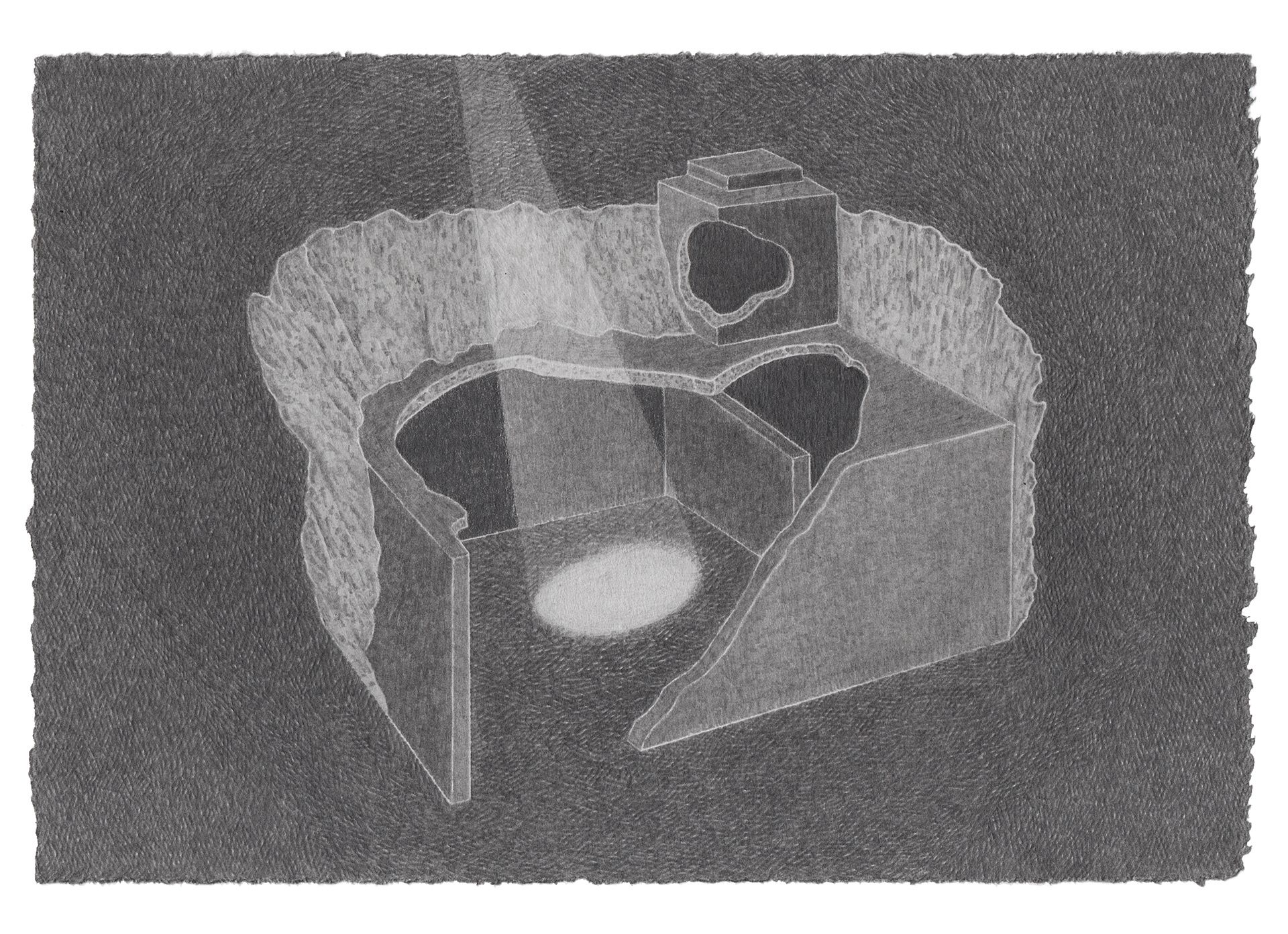

I’ve incorporated such tricks into my sculptural works, such as “Silver Bullet Test Site” (2017), where I created a point perspective optical illusion of an underground basement shelter. With this work, I aimed to explore the relationship between safety and horror, crafting a space that is both welcoming and menacing.

While your work primarily addresses ideas of “safety,” there are often areas of past destruction within the worlds you build. How are safety and destruction linked within your work?

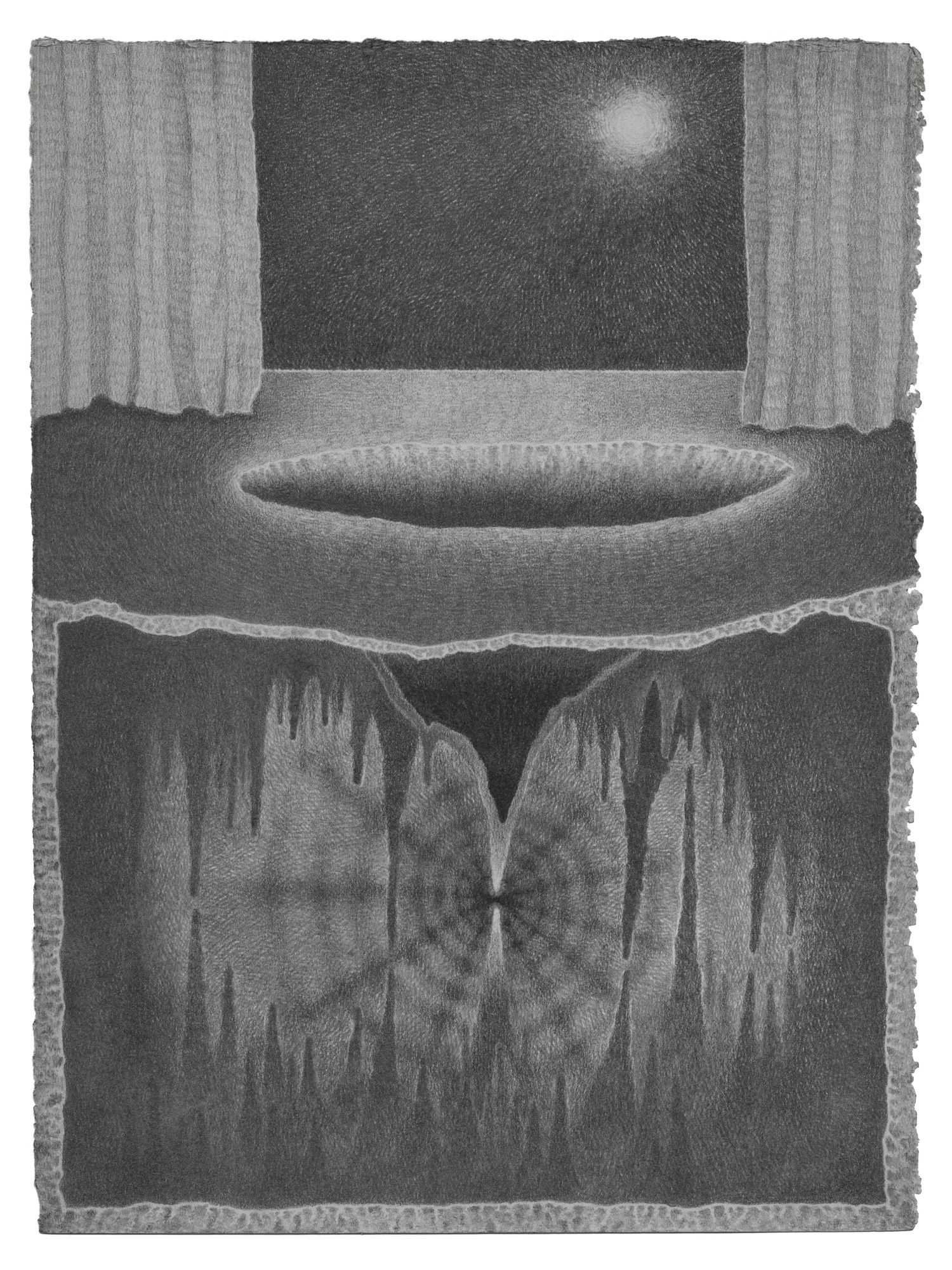

When one thinks about safety, it is unavoidably linked to the question, “from what?” I’m interested in the tension that exists there—trying to understand what sorts of destruction occur to obtain a certain kind of safety. My series of works on paper and panel titled “Stages of Fallout” (2019-2024) embodies this concept. The works in this series began after I discovered a fallout shelter manual titled “The Family Fallout Shelter,” created by the U.S. Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization in the 1950s. The manual features illustrations that showcase various designs for underground fallout shelters. What fascinated me most when I first found this manual was that, to depict these structures, the illustrator created “bombed-out” areas or bites taken out of the landscape to reveal the underground spaces. I borrow this method in the series to explore the complex interplay between these ideas.

What role does audience interaction or perception play in your work?

Since my practice often shifts between two and three-dimensions, and since my work deals closely with space, I’ve been interested in how an audience might navigate the work either physically or through imagination. I’ve been really thinking about how my sculptural works are different from drawings in that the drawings somehow allow the imagination to run free, while the body and its relationship to my sculptural installations is very much dictated and fixed. I wouldn’t really say that I prefer one approach or the other, but I’ve become increasingly interested in the space between the two. Ultimately, I seek to create environments where the boundaries between imagination and physicality blur, allowing for a richer, more nuanced engagement with the themes I explore.

How did your drawing practice start?

I’ve always drawn throughout my life, but I really started taking it seriously when a friend of mine visited my studio in 2019, at a moment in which I was particularly stuck in my practice, and challenged me to make a single drawing each day. Up until then I was making larger-scale theatrical installations as well as miniature sculptures out of balsa wood, so this challenge really shifted the way I worked, and the speed in which I could express ideas. I found that the more I drew the more I learned from the process and the more exciting it felt as my technique began to improve. I like how a drawing can be made in very little time, or that you might refine and meditate on it for as long as you like.

You mention “TV static” playing a large role in your visual aesthetic. What drew you to static and what deeper meaning does it hold to you?

I realized that when I began taking drawing seriously, my preferred method of mark making was through cross-hatching. Something about its ability to express a variety of textural shifts and spatial fields really appealed to me. After a long time working with this process, I started to think about how it conceptually operates within the images I create. It seems to shapeshift and take form as both terrestrial and celestial scapes, while also transforming into the digital space of TV static. I love the tension and vibration this creates within an image, and how it can connect all of these ideas of space into a single image. There is something about this “TV static” effect that ultimately takes you into a psychological space.

You’ve recently taken a break from art making. What have you learned from stepping back for a moment?

I started the break after experiencing carpal tunnel in my wrists from long hours of drawing, and the break persisted as world events got darker and inspiration seemed really hard to find. I’ve really been asking myself and wondering about the purpose of art during these times. What's the use of creating amidst so much carnage and horror? I think that there are times when a break is necessary in order to engage with the world in a more direct way. There's often the perception that an artist needs to be working all the time and, especially these days, posting and sharing. I can’t say I know exactly what I've learned yet, except that perhaps sometimes not making art is the most logical and moral answer.

I believe congratulations are in order, as you recently were awarded a Lower East Side Printshop Keyholder residency in NYC! It feels like your drawing practice will meld so naturally to printmaking. What goals do you have for yourself during this residency?

Thank you! Yes, I'm very excited to begin printmaking again — I don’t think I've made any prints since graduating from my undergraduate program in 2012! My greatest goal for the residency is to learn the Intaglio process. I think that the way I draw could translate beautifully in etching form, and I'm curious to see how the process might be different. I’m really taking this as an opportunity to learn, jumpstart my practice after this extended break, and just see where it all takes me!

Do you listen to music or podcasts while you work?

I do! My musical tastes seem to vary greatly depending on the days’ vibe. I’ll often listen to classical, jazz or folk. I’ve had Emahoy Tsege Mariam Gebru’s Ethiopiques album on repeat for years. I’ll also listen to Joni Mitchell or Tracy Chapman (artists my mother and I would listen to and belt out in the car when I was younger).

In addition to being an accomplished artist, you are also a director and curator at Ortega Y Gasset Projects! Can you tell us about this experience and how it all came to be?

I joined Ortega Y Gasset Projects in 2019 after having a solo exhibition with the gallery in 2018. My former grad school professor and mentor Leeza Meksin is one of the founding members, and with her encouragement I applied to one of the gallery’s yearly calls for solo exhibitions. The team enjoyed working with me and later invited me to join as co-director. Working with OyG has been an incredible journey – we are a nonprofit organization run entirely by working artists, with the mission of exhibiting under-recognized, under-represented, and marginalized artists. I’ve met so many incredible friends and colleagues through this work, and we seem to grow more and more each year. I’m excited to see in what ways we can further this work, and how we might better support artists moving forward.

Has there been a teacher or mentor who has been particularly helpful to your practice?

When I was an undergraduate student in Chicago, I took a class with the artist Anne Wilson. I started working as her studio assistant during my final semester, creating intricate and fine stitched work in her studio. We continued to work together for many years following my graduation. Anne has been an incredible inspiration, and has taught me so much about how to look, take time, meditate, and explore the deep meanings and histories embedded within materials. I think of her and our work together often, and can definitely see her inspiration appearing in my work.

If you could magically live with any work of art in the world, what would it be?

Wow, that's too hard to pick! But the first image that came to mind, perhaps a bit cliché, is Matisse’s Dance. I guess I want to dance naked!

image by Colin Conces